It’s the cheapest London property you'll ever own. It's possibly the only London property you'll ever own. It’s 24sq ft, there's no natural light, and hundreds of near neighbours - but it's yours… for a while.

So, can I interest you in a grave?

Anyone committed to living their life in London should give at least half a thought to spending the afterlife here too. For those considering cremation, it’s very little trouble – just make sure your nearest and dearest have permission from the owner before scattering ashes over your favourite pub garden. If burial feels right, it’s worth knowing that the options are slimmer than they might seem.

First, there’s the cost. A plot in one of Southwark’s three open sites, for example, costs more than £4,000 for a standard 50 years of “exclusive burial rights”, with extra fees in store for the burial itself. As with most of London’s property market, couples have the upper hand; a single plot will hold two coffins. Then there are the exclusive rights – once they expire, spare space in a private grave can be resold.

This was once only a distant possibility. After the cemetery building boom in the Victorian era, plots were sold with rights in perpetuity, chiming with religious beliefs in eternal rest. The gothic garden cemeteries of the 1800s were designed as a response to the crowded churchyards of the inner city, which were overstuffed to the point of endangering public health.

The first set, known today as the Magnificent Seven, covers more than 250 acres of land in the suburbs. Their mausoleums and monuments plead for permanent, personalised memorials. (The deterioration of Nunhead Cemetery, which went bust and eventually became the woodland it is today, would surprise its early patrons, particularly those who forked out a small fortune to be buried in its crypt. Now a ruin, the walls drip with poisonous lime and the lead coffins have been plundered by grave robbers.)

Less than two centuries on, however, vacancies are scarce, and any spare space is put to use. If you fancy eternal repose among eminent Victorians at Kensal Green or Highgate, prepare to spend upwards of £20,000. Even more modern graveyards are straining for space. For many Londoners it is almost impossible to be buried close to home, family or community. Lambeth is, in the words of an audit by the University of York, “full”, as are most of the inner boroughs north of the Thames.

There’s a similar problem across the country, but London boroughs are unique in having the power to do something about it. Councils here have the right to reuse graves that are more than 75 years old. It means letting go of taboos around sharing space with a stranger; the defining feature of what were once called paupers’ funerals and are now known as public graves.

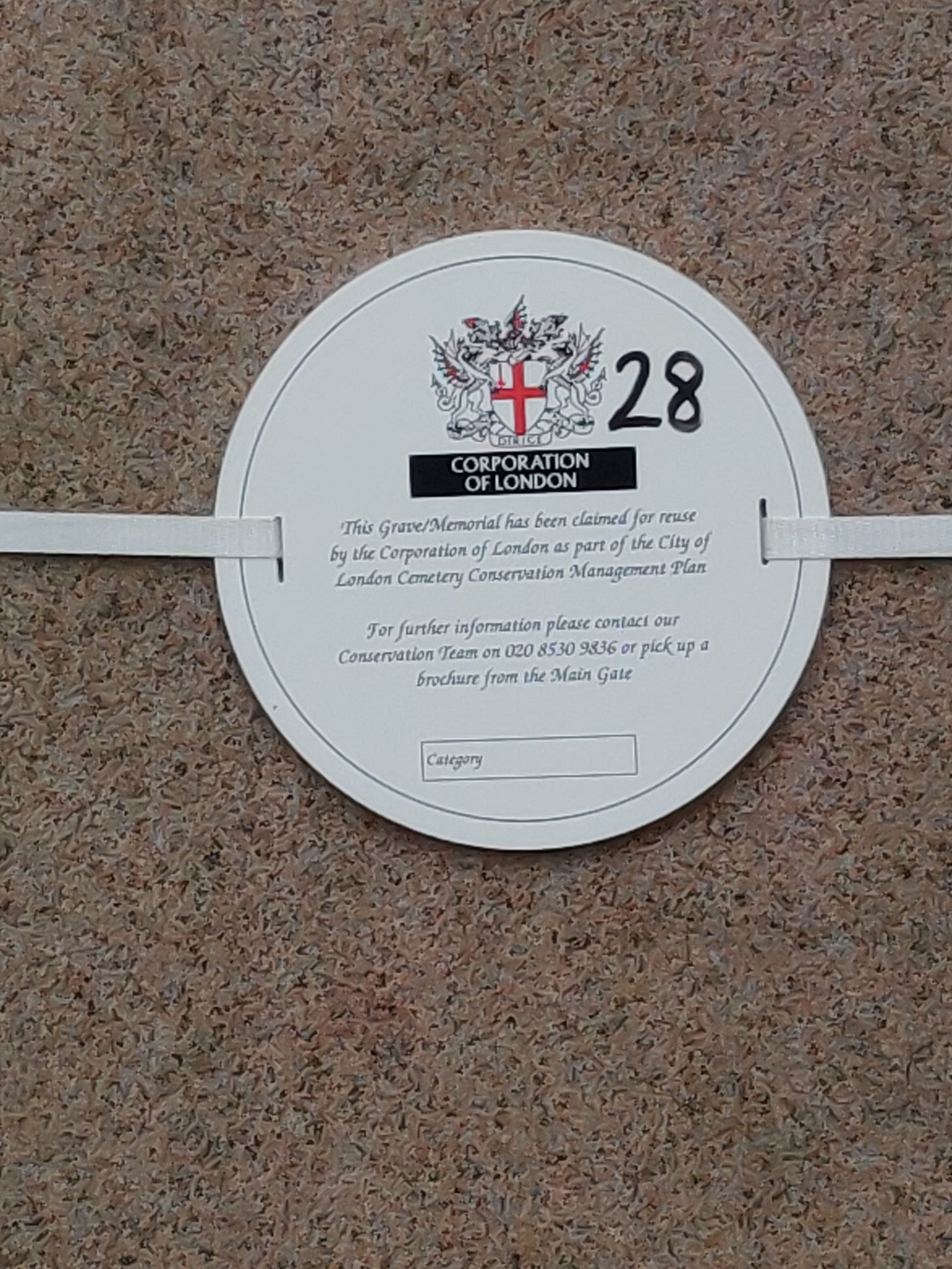

The City of London Cemetery in Manor Park is one of the few to take advantage of this quirk of London law. It is a truly massive 200-acre site, but space is still a pressing concern. Since 2009, the cemetery’s custodians have been using a “ground-breaking” (no, really, that’s the word the corporation used) “lift and deepen” approach to older graves. It’s sensitive work: notices are placed on gravestones to make sure families have every opportunity to object, and when it’s done the two burials, old and new, share a gravestone. The inscriptions sit either side of the stone, more than 75 years and only inches apart.

Reuse also disturbs the finality of it all. Burial feels like an ending – you don’t need to be spiritual to grasp the metaphor of a tonne of earth covering up a corpse. “Lift and deepen” uncloaks that myth and exposes reality and rot. Remains - if they exist - are removed, the grave is deepened, and the original occupant is reburied below their new companion. Seventy five years, it should be noted, is long enough for a body to be skeletonised, given the right conditions and coffin.

Perhaps Londoners should be more used to sharing space with dead strangers. Like the rats, they’re everywhere. Fifteen years ago, at a sleepover, a school friend led me and a handful of other girls – all Buffy fans and wannabe witches – out of her home and into the night. Her house had no front garden, but a small gated-off square of closely grown trees stood between it and the road. In the gloom, mostly hidden by the undergrowth, were graves.

It was a thrilling moment for a spooky child, but I shouldn’t have been surprised. London is a city of the dead. Humans have lived and died here, on and off, for at least 5,000 years. Inevitably there are thousands of people entombed in the earth below us, and it's surprisingly easy for an entire burial ground to disappear without a trace.

Think of any historic church in central London, hemmed in on all sides by maddeningly expensive commercial property. A few centuries ago they sat in churchyards full of graves, marked and unmarked. Now, they’ve vanished. The London Lost Churches Project records more than 100 missing churches in the City alone. While many of the dead were exhumed and reburied at the City of London Cemetery in the 1860s, some were left where they were.

Others were lost centuries earlier. The Spitalfields Charnel House, excavated in 1999, was a medieval answer to the problem of grave space. Bones dug up to make way for new burials were preserved in the crypt to await Judgement Day. In reality they were decanted long before then, when the hospital was closed in the sixteenth century, but the ruins of the crypt are preserved by Spitalfields Market.

Standing there now, it’s difficult to believe that the burial ground was once outside London, deliberately placed beyond the city gates. With each expansion the new dead have been pushed further out into the suburbs, and the old dead further down into the ground. Now it’s only redevelopment that reminds us of them.

When Crossrail was being dug, teams of archaeologists swept in whenever remains were discovered – more than 3,000 burials were uncovered at Liverpool St Station alone. The space crisis struck again when it came time to rebury the excavated skeletons; despite having the good sense to be buried in London, these poor souls unfortunately ended up on Canvey Island, near Southend.

Some of the dead aren’t even below ground. The Museum of London catalogues 20,000 human remains; the British Museum has 6,000. Pop into Westminster Cathedral and the parboiled body of John Southworth rests in a chapel to your left. Their ever presence in living, breathing London certainly puts sharing a grave in perspective.

If we’re content to live our lives with the dead beneath our feet, why should death be any different?